Techniques for Identifying Mutants

What is mutants?

Any organism carrying a mutation is called a mutant, whereas the normal strain isolated from nature without the mutation is the wild type. Some mutants are easy to identify because the phenotype, or physical appearance, of the organism or the colony has changed from the wild type.

For example, some bacterial colonies appear red because they produce a red pigment. Treat the colonies with a mutagen and, after plating on nutrient agar, mutants form colorless colonies. However, not all mutants involve an obvious phenotype change.

Plating Techniques Select for Specific Mutants or Characteristics

If a mutation does not produce a visible change, how does one “see” a mutation and then isolate the mutant cell? In microbiology, there are ways to select for (identify and isolate) a single mutant from among thousands of possible cells or colonies. Let’s look at two selection techniques that make this search possible.

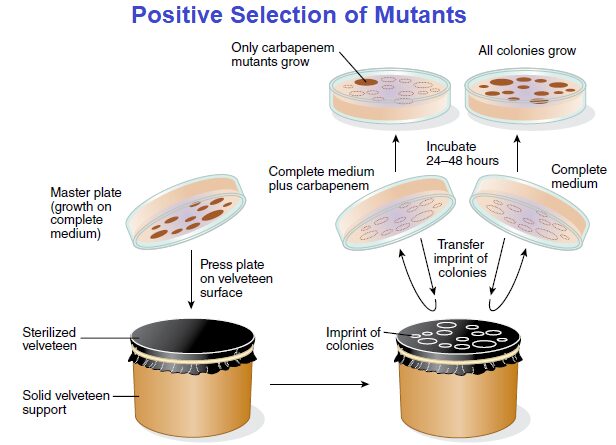

First, in both techniques, the chemical composition of the transfer plate is important for visual identification of the colonies being hunted. The use of a replica-plating device makes the identification possible. The device consists of a sterile velveteen cloth or filter paper mounted on a solid support.

When an agar plate (master plate) with bacterial colonies is gently pressed against the surface of the velveteen, some cells from each colony stick to the velveteen. If another agar plate then is pressed against this velveteen cloth, some cells will be transferred (replicated) in the same pattern as on the master plate.

Now, suppose that you want to find a nutritional mutant that cannot grow without the amino acid histidine. This mutant (written his–) has lost the ability that the wild-type strain (his+) has to make its own histidine. Such a mutant having a nutritional requirement for growth is called an auxotroph (auxo = “increase”; troph = “nourishment”), whereas the wild type is a prototroph (proto = “original”).

Visually, there is no difference between the two strains when they grow on a complete medium with histidine. However, you can visually identify the auxotroph by using a negative selection plating technique, as described in FIGURE.

As another example, suppose you want to see if there are any potentially dangerous carbapenem resistant bacteria in a hospital ward. Carbapenem resistant bacteria, including some strains of E. coli, have become difficult to treat because these bacteria are resistant to most all antibiotics. This includes carbapenem, which is called a “last resort” antibiotic because it is the last useful antibiotic when all others have failed in treating a patient.

Again, phenotypically, there is no difference between those strains sensitive to carbapenem and those resistant to the antibiotic when they grow on a complete medium without carbapenem. However, a positive selection plating technique permits visual identification of such carbapenem-resistant mutants because they will grow on a complete medium containing carbapenem, as described in FIGURE.

The Ames Test Can Identify Potential Mutagens

Besides a means to identify mutants, there are ways to identify mutagens. Some years ago, scientists observed that about 90% of human carcinogens—agents causing tumors in humans—also induce mutations in bacterial cells. Working from this observation, Bruce Ames of the University of California developed a procedure to help identify potential human carcinogens by determining whether the agent can mutate bacterial auxotrophs.

The procedure, called the Ames test, uses an auxotrophic (histidine-requiring) strain (his–) of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium. If inoculated onto a plate of nutrient medium lacking histidine, no colonies will appear because in this auxotrophic strain the gene inducing histidine synthesis is mutated and hence not active.

In preparation for the Ames test, the potential carcinogen is mixed with a liver enzyme preparation. The reason for doing this is because chemicals often become tumor causing and mutagenic in humans only after they have been modified by liver enzymes.

To perform the Ames test, the his– strain is inoculated onto an agar plate lacking histidine. A well is cut in the middle of the agar, and the potential liver-modified carcinogen is added to the well (or a filter paper disk with the chemical is placed on the agar surface).

The chemical diffuses into the agar during a 24- to 48-hour incubation. If bacterial colonies appear, one can conclude the agent mutated the bacterial his– gene back to the wild type (his+); that is, revertants were generated that could again encode the enzyme needed for histidine synthesis. Because the agent is a mutagen in bacteria, it is therefore a possible carcinogen in humans. On the other hand, if bacterial colonies fail to appear, one can assume that no mutation took place.

Reference and Sources

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carbapenem_resistant_enterobacteriaceae

Also Read:

- Gram staining

- Measurements of microbial growth

- what is microbiology?

- How to Build a Microorganism?

- Overview of Viroids, Satellites and prions

- Virus: Introduction, Properties and Classifications

- Agglutination reaction: Definition, Uses and Application

- Microbial Identification and Strain Typing Using Molecular techniques

- Classification of viruses on the basis of genome

- Comparison Between the Domains Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya

- Bacterial Growth Curve: Definition, Phases and Measurement

- Microbiology Disciplines: Bacteria, Viruses, Fungi, Archaea and Protists