Morphology

Clostridium is a genus of Gram-positive, rod-shaped, spore-forming bacteria within the phylum Firmicutes. These anaerobic bacteria thrive in oxygen-deprived environments. The name “Clostridium” derives from the Greek word kloster, meaning spindle, reflecting their typical shape. Clostridium species are widely distributed in soil, water, and the gastrointestinal tracts of humans and animals. While some species are beneficial in natural ecosystems, others act as opportunistic pathogens. Notably, Clostridium botulinum causes botulism, a severe neurotoxin-mediated illness, and Clostridium difficile is a leading cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis in healthcare settings.

Clostridium species’ morphology is typical of Gram-positive bacteria. Here are some notable morphological features:

- Shape: They are typically rod-shaped, which means they look like elongated cells with straight or slightly curved edges. The rods might differ in size, but they are often bigger than other bacteria.

- Gram Staining: They are Gram-positive, indicating that they hold the crystal violet stain during the Gram staining process. This is owing to the presence of a thick peptidoglycan layer in their cell walls.

- Spore Formation: One distinguishing characteristic of Clostridium bacteria is their capacity to produce endospores, which are extremely durable structures that enable the bacterium to endure severe conditions. These spores are generated in unfavorable circumstances, such as nutrient depletion or exposure to harmful environmental factors like heat, and they can stay dormant until conditions become favorable for germination.

- Motility: Several Clostridium species are motile and have flagella that allow them to travel effectively in liquid surroundings. Not all species in the genus are motile.

- Capsules: Some Clostridium species produce capsules, which are protective structures that surround the cell wall. Capsules assist the bacteria in evading the host’s immune system and offer resistance to dehydration and other environmental conditions.

- Anaerobic Growth: They are strict anaerobes, which means they flourish in the absence of oxygen. Oxygen is poisonous to them, and exposure to it can slow their development or even result in death. As a result, they are frequently present in environments such as soil, sediments, and animal gastrointestinal tracts, where oxygen levels are low.

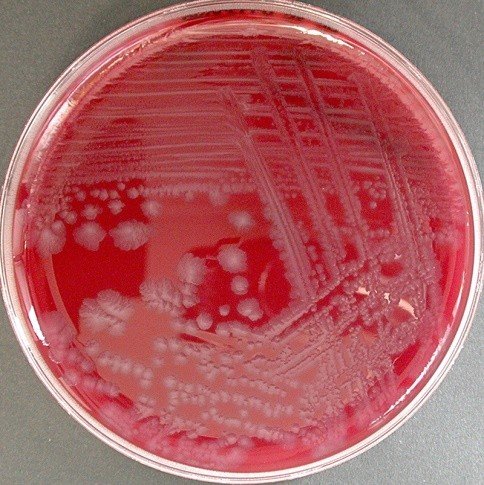

- Cultural Characteristics: When cultivated in a laboratory setting, they typically form circular, smooth-edged colonies. The colour and appearance of these colonies may differ depending on the species.

Ecology and Habitat

- Free-living Clostridium: Clostridium species are ubiquitous and can be found in a variety of locations worldwide. Oxygen tolerance in these species varies significantly, with some being strict anaerobes. For this reason, the oxygen concentration in a given environment will impact the kinds present.

- Most Clostridium species are saprophytes, meaning they derive nutrients from decaying plants and animals in soil and other aquatic habitats. In these conditions, the bacteria decompose a variety of organic substances, contributing to humus soil.

- Aside from contributing to humus soil, free living Clostridium discovered in earth have been shown to play a significant role in nitrogen fixation. For example, Clostridium pasteurianum, a free-living Clostridium species, can fix atmospheric nitrogen and transform carbohydrates into other compounds and molecules such as carbon dioxide, acetate, and butyrate.

- Since most of these species are anaerobes, they accomplish this through fermentation. Other species of the genus Clostridium that are capable of nitrogen fixation include: C. beijerinkii, C. acetutlycumFree-living Clostridium species capable of nitrogen fixation possess the nif gene.

- Aside from soil and water (freshwater sediments), free-living Clostridium species can be present in a variety of wet settings, including some plant roots. Some of the species found in a plant’s roots are harmful to the plant. For example, C. puniceum causes potato soft rot.

Pathophysiology of Clostridial Infections

- The pathogenic species generate tissue-destructive and neural exotoxins, which cause the symptoms of the disease. When the tissue oxygen tension and pH are low, Clostridia can turn pathogenic.

- In ischemic or devitalized tissue, as seen in primary arterial insufficiency or following severe penetrating or crushing wounds, such an anaerobic atmosphere may arise.

- Patients are more susceptible to clostridial infection the deeper and more serious the injury is, especially if there is any little foreign material contamination.

- Ilicit drug injection can also cause clostridial illness.

- Home canned foods that contain toxins produced by clostridia can cause serious non-infectious illness.

- Clostridia-Induced Diseases Clostridial infections can result in a number of illnesses, such as:

- (C. botulinum) botulism

- Colitis brought on by Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile

- Gastroenteritis

- Soft tissue infections

- Tetanus caused by C. tetani

- Clostridial necrotizing enteritis caused by C. perfringens type C

- Neutropenic enterocolitis (typhlitis) caused by C. septicum

- Minor, self-limited gastroenteritis caused by C. perfringens type A is the most common clostridial infection. Although they can be lethal, severe clostridial illnesses are uncommon.

- Abdominal conditions like bowel perforation can involve C. ramosum, C. perfringens, and a variety of other organisms.

- perfringens can cause muscle necrosis and soft tissue infections, which are marked by clostridial myonecrosis, myositis, and crepitant cellulitis.

- Bloodborne C. septicum from the colon can induce skin and tissue necrosis.

- The role of Clostridia in typical mild wound infections, where they are also present as part of a mixed flora is unknown.

- Clostridial infections acquired in hospitals are on the rise, especially among postoperative and immune-compromised patients.

- Intestinal perforation and blockage can result in severe clostridial sepsis.

Clostridium Bacteremia: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Resistance

Pathogenesis and Virulence

- Exotoxins (e.g., alpha-toxin) and enzymes destroy tissues and evade immune responses.

- Spore formation increases survival and resistance.

Host Immune Response

- Innate Immunity: Macrophages and neutrophils detect PAMPs.

- Adaptive Immunity: T and B cells produce specific antibodies for long-term protection.

Diagnosis

- Clinical Evaluation: History and symptoms guide initial diagnosis.

- Laboratory Tests: Blood cultures, PCR, ELISA, and toxin detection assays confirm diagnosis.

Prevention

- Aseptic Techniques: During surgery and wound care.

- Antibiotic Stewardship: To maintain gut flora.

- Infection Control: Especially in immunocompromised and hospitalized patients.

Clostridium difficile Colitis: Pathogenesis and Host Defense

Overview

- Originally termed Bacillus difficilis due to difficult culturing.

- Common cause of healthcare-associated diarrhea.

Pathogenesis

- Transmitted via oral-fecal route.

- Spores survive gastric acid and germinate in the intestine.

- Disruption of normal flora by antibiotics facilitates colonization.

- Toxins A (TcdA) and B (TcdB) cause inflammation and diarrhea.

Diagnosis

- Sample Collection: Stool or tissue under anaerobic conditions.

- Culture and Microscopy: On selective media.

- Toxin Assays: ELISA, PCR for TcdA/TcdB.

Prevention

- Hand Hygiene: In healthcare environments.

- Vaccination: Tetanus toxoid for tetanus prevention.

- Food Safety: Proper canning and storage to prevent botulism.

- Antibiotic Control: Avoid unnecessary antibiotic use.

Industrial Applications of Clostridium

1. Production of Bio hydrogen

- Clostridium butyricum and C. beijerinckii are well-known for their dark fermentation-based biohydrogen production. Choi et al. demonstrated in a 2025 study that coculturing these organisms with lactic acid bacteria greatly increased hydrogen production, reaching rates of up to 89. 6 mL H₂/g volatile solids when utilizing food waste as a substrate.

- These bacteria produce volatile fatty acids and hydrogen through anaerobic carbohydrate fermentation. The synergistic interplay aids in suppressing hydrogen-consuming organisms, such as methanogens, hence stabilizing the process in pilot and lab-scale bioreactors.

- This is practically useful in biogas plants that turn organic waste into clean hydrogen fuel and in renewable energy systems.

2. Solvent Generation (ABE Fermentation)

- acetobutylicum and C. beijerinckii are traditional microorganisms employed in the fermentation of acetone, butanol, and ethanol (ABE). C. saccharobutylicum DSM 13864 produced solvents effectively from sagostarch in a continuous fermentation process, resulting in significant quantities of acetone and butanol.

- These bacteria have a biphasic metabolism that is activated by pH changes and consists of acidogenesis followed by solvent genesis. Butanol, the main product, is a potential biofuel because of its greater energy density and suitability for current fuel infrastructure.

- Biochemical industries that concentrate on producing renewable fuels and solvents from agricultural waste employ such Clostridium-based procedures.

3. Fermentation of Syngas (Gasto Liquid Bioconversion)

- Clostridium autoethanogenum is a crucial organism in the fermentation of syngas, converting industrial waste gases rich in CO, CO₂, and H₂ into ethanol and other chemicals. A significant industrial use of this method is found in LanzaTech’s commercial platforms, where modified strains ferment bioethanol from steel mill off gases.

- These microorganisms have the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway, which enables efficient carbon fixation in anaerobic environments. By connecting carbon capture with energy production in industries like steel, cement, and waste gas treatment, the technique provides a sustainable way to transform carbon emissions into useful biofuels.

Conclusion

Clostridium encompasses a wide range of species with diverse roles in ecology, medicine, and industry. While certain species are formidable pathogens responsible for severe human diseases, others contribute to sustainable energy and environmental applications. Understanding the morphology, pathogenic mechanisms, diagnostic techniques, and preventive strategies is essential for managing Clostridium-related infections and harnessing its industrial potential.

FAQ: Clostridium

Q1. What is the morphology of Clostridium species?

Clostridium are Gram-positive, rod-shaped, spore-forming bacteria. They are strict anaerobes, often motile with peritrichous flagella, and some species produce protective capsules that enhance survival in harsh conditions.

Q2. Where are Clostridium bacteria found in nature?

Clostridium species are widely distributed in soil, water, sediments, and the gastrointestinal tracts of humans and animals. Free-living species contribute to nitrogen fixation and organic matter decomposition, while pathogenic species cause human diseases.

Q3. Which diseases are caused by pathogenic Clostridium species?

- C. botulinum → Botulism (neurotoxin-mediated illness)

- C. tetani → Tetanus

- C. difficile → Antibiotic-associated colitis and diarrhea

- C. perfringens → Gas gangrene, food poisoning, and enteritis

- C. septicum → Neutropenic enterocolitis and bacteremia

Q4. What makes Clostridium species pathogenic?

Their pathogenicity mainly stems from exotoxins (e.g., botulinum toxin, tetanus toxin, alpha-toxin) and enzymes that destroy tissues, evade host immunity, and cause systemic damage. Spore formation also enhances their persistence in hostile environments.

Q5. How are Clostridial infections diagnosed?

Diagnosis is based on:

- Clinical evaluation (symptoms, history).

- Laboratory methods: Anaerobic culture, Gram staining, toxin detection (ELISA, PCR, immunoassays), and blood cultures in systemic infections.

Q6. What is Clostridium difficile colitis?

Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) is a major healthcare-associated diarrhea caused by toxins A (TcdA) and B (TcdB). It occurs when antibiotic use disrupts normal gut flora, allowing C. difficile to colonize and release toxins that damage intestinal lining.

Q7. How can Clostridial infections be prevented?

- Aseptic techniques in surgery and wound care

- Hand hygiene in hospitals

- Food safety (proper canning/storage to avoid botulism)

- Vaccination (tetanus toxoid for tetanus)

- Antibiotic stewardship to prevent C. difficile infections

Q8. What are the industrial applications of Clostridium?

Clostridium species are biotechnologically important:

- Biohydrogen production (C. butyricum, C. beijerinckii)

- Acetone-Butanol-Ethanol (ABE) fermentation (C. acetobutylicum)

- Syngas fermentation into bioethanol (C. autoethanogenum, used in LanzaTech)

These processes contribute to biofuel, renewable energy, and green chemistry industries.

Q9. Can Clostridium be beneficial to the environment?

Yes. Free-living Clostridium species such as C. pasteurianum fix nitrogen and help in soil fertility. Industrially, Clostridium-based fermentation aids in reducing carbon emissions by converting waste gases into biofuels.

Q10. Why is studying Clostridium important in microbiology?

Clostridium has a dual role:

- Medical importance as pathogens causing life-threatening diseases.

- Industrial importance in renewable energy, waste management, and biochemical production. Understanding their morphology, pathogenesis, and applications is vital for both clinical microbiology and biotechnology research.