Overview of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) is a viral respiratory illness caused by a coronavirus, first identified in 2002–2003. The SARS outbreak provided a key example of how viruses evolve, adapt, and cross species barriers, leading to widespread human disease.

- In November 2002 a mysterious pneumonia was seen in the Guangdong Province of China, but the first case of this new type of pneumonia was not reported until February 2003.

- Thanks to the ease of global travel, it took only a couple of months for the pneumonia to spread to more than 25 countries in Asia, Europe, and North and South America.

- This newly emergent pneumonia was labeled “severe acute respiratory syndrome” (SARS), and its causative agent was identified as a previously unrecognized coronavirus (CoV), the SARS-CoV.

- Almost 10% of the roughly 8,000 people with SARS died.

- However, once the epidemic was contained, the virus appeared to “die out,” and with the exception of a few mild, sporadic cases in 2004, no additional cases have been identified.

- From where does a newly emergent virus come? And why did this viral disease apparently disappear?

- Coronaviruses are large, enveloped viruses with positive strand RNA genomes. They are known to infect a variety of mammals and birds.

- Researchers suspected that SARS-CoV had “jumped” from its animal host to humans.

- To test this hypothesis, samples of animals at open markets in Guangdong were taken for nucleotide sequencing.

- These studies revealed that cat like animals called masked palm civets (Paguma larvata) harbored variants of the SARS-CoV.

- Although thousands of civets were then slaughtered, further studies failed to find widespread infection of domestic or wild civets.

- In addition, experimental infection of civets with human SARS-CoV strains made these animals ill, making the civet an unlikely candidate for the reservoir species.

- Such a species would be expected to harbor SARS-CoV without symptoms so that it could efficiently spread the virus.

- Bats are reservoir hosts of several zoonotic viruses (viruses spread from animals to people).

- Thus it was perhaps not too surprising when in 2005 two groups of international scientists independently demonstrated that Chinese horseshoe bats (genus Rhinolophus) are the natural reservoir of a SARS like coronavirus.

- When the genomes of the human and bat SARS-CoV are aligned, 92% of the nucleotides are identical.

- More revealing is alignment of the translated amino acid sequences of the proteins encoded by each virus.

- The amino acid sequences are 96 to 100% identical for all proteins except the receptor-binding spike proteins, which are only 64% identical.

- The SARS-CoV spike protein mediates both host cell surface attachment and membrane fusion.

- Thus a mutation of the spike protein allowed the virus to “jump” from bat host cells to those of another species.

- It is not clear if the SARS-CoV was transmitted directly to humans (bats are eaten as a delicacy, and bat feces are a

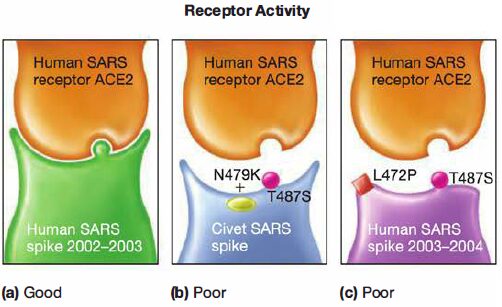

traditional Asian cure for asthma) or if transmission to humans occurred through infected civets. - The region of the SARS-CoV spike protein that binds to the host receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE2), forms a shallow pocket into which ACE2 rests.

- The region of the spike protein that makes this pocket is called the receptor binding domain (RBD).

- Approximately 220 amino acids within the RBD, only four differ between civet and human.

- Two of these amino acids appear to be critical.

- Compared to the spike RBD in the SARS-CoV that caused the 2002-2003 epidemic, the civet spike has a serine (S) substituted for a threonine (T) at position 487 (T487S) and a lysine (K) at position 479, instead of asparagine (N), N479K.

- This causes a thousand-fold decrease in the capacity of the virus to bind to human ACE2.

- Furthermore, the spike found in SARS-CoV isolated from patients in 2003 and 2004 also has a serine at position 487 as well as a proline (P) for leucine (L) substitution at position 472 (L472P).

- These amino acid substitutions could be responsible for the reduced virulence of the virus found in these more recent infections.

- In other words, these mutations could be the reason the SARS virus appears to have “died out.”

Reference and Sources

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/7570445_Bats_Are_Natural_Reservoirs_of_SARS-Like_Coronaviruses

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5875893/

- https://covid.us.org/2020/06/29/yes-the-coronavirus-really-is-that-bad/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_viruses

Also Read:

- Animal and plant viruses, prions, and viroids

- Cider: Production, Extraction, Fermentation and Maturation

- DNA Replication in eukaryotes: Initiation, Elongation and Termination

- Spectroscopy: Introduction, Principles, Types and Applications

- Nosocomial Infection: Introduction, Source, Control and Prevention

- Measurements of microbial growth

- Whole-Genome Shotgun Sequencing: overview, steps and achievements